CLEAR LAKE, Iowa – In the wake of rumors that the Trump Administration intends to fully declassify files on the JFK, RFK, and MLK assassinations, watchdog groups and NGOs are looking for answers on one of the last remaining great American mysteries: the Day the Music Died.

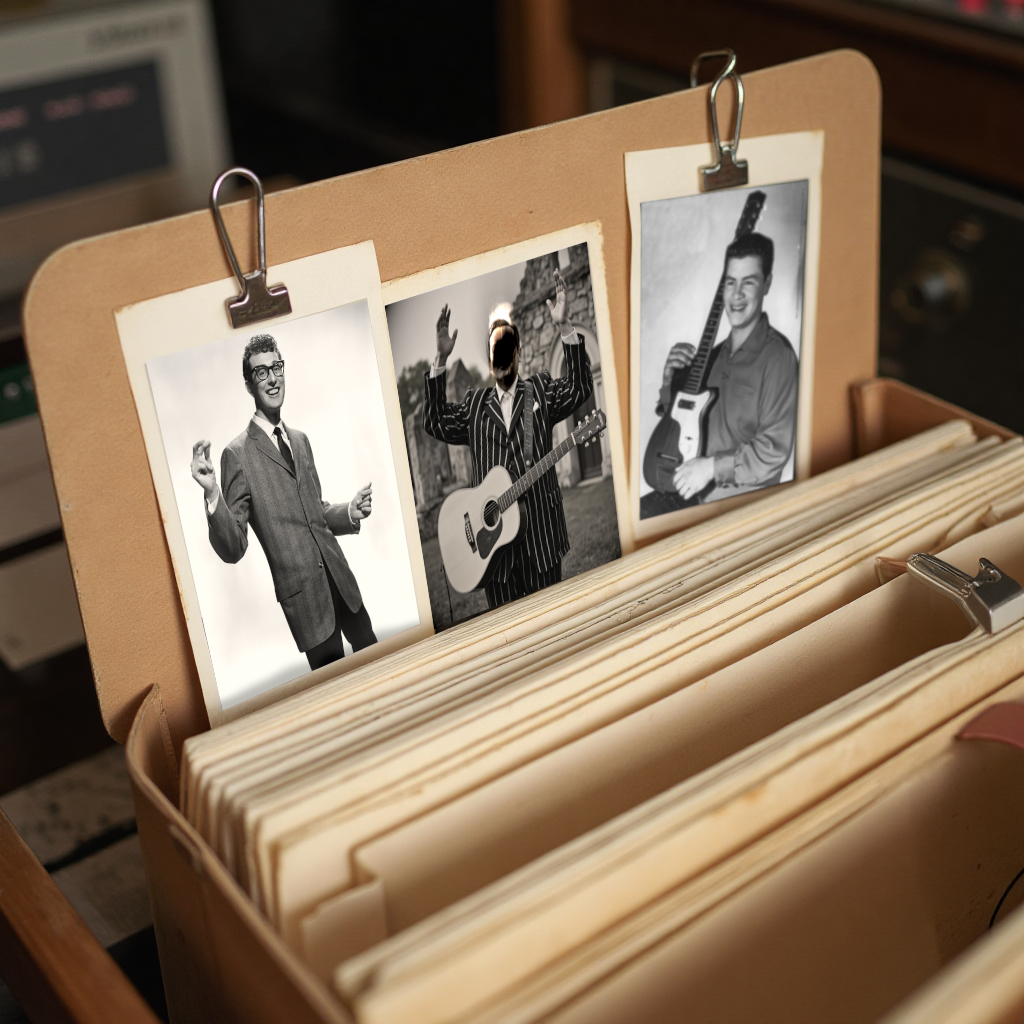

On a snowy February 3rd, 1959, a single engined Beechcraft 35 Bonanza aircraft left the municipal airport in Mason City, Iowa. The destination was Fargo, the nearest airport to Moorehead, Minnesota. The passengers on board included musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and Jiles Perry Richardson Jr., better known as The Big Bopper. The young superstars were on a barnstorming, no-days-off rock n’ roll tour of the Upper Mid-West, but these three would not make the next date at the Moorehead Armory. The wreckage of the Beechcraft was found only six miles from the airport, spread across an icy Iowa field.

The tour – and the artists’ musical legacies – continued on. Questions lingered about the crash and the fate of the victims, however. For the past sixty-five years, brave truth seekers have been looking for answers.

Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens both died on impact, we don’t care about them. It’s the Big Bopper that’s a problem.

Someone Watching Over You

Some of the earliest post-crash Bopper sightings came from his childhood hometown of Beaumont, Texas. At numerous events in 1963 and 1964, Beaumont High cheerleaders reported hearing a warbling “Hellooooo bayyyyybeeeeee!” while they were showering. Searches of the bathrooms turned up nothing, except on one occasion when the words “But, but, but…oh honey” were found scrawled on a steamy mirror. This apparition was locally called “The Big Boo-per” and “That Horny Ghost” by area teens, but the spirit vanished by late 1964.

An even more sinister theory of the case involves The Big Bopper’s accursed quest for eternal life. Most music critics at the time believed that Mr. Bopper’s hit song, “Big Bopper’s Wedding”, was a juvenile story about a character who didn’t want to tie the knot. That’s certainly the most popular reading. The final line of the song, however – “Partnah, I don’t believe I do. Let me outa here!” – may speak to a different kind of enslavement he’s trying to escape: the enslavement of flesh and mortality.

Confidential sources with deep ties to the Dark Rockabilly Arts scene claim that The Big Bopper killed seven men between 1952 and 1958, imbuing their souls in a Gibson LG3 flattop guitar. When his physical body died in the plane crash, his eternal soul was safe in the instrument.

Beggar To A King

It may have taken many years for The Big Bopper to gather the strength to incorporate a physical form, which could account for some of the earlier hauntings by an invisible presence. There is evidence, however, that his powers grew when really dumb songs charted.

Billboard appearances by “The Pied Piper” (1966) and “Come On Down To My Boat” (1967) coincided with massive spikes in unexplained disappearances of ladies’ undergarments from dressing rooms, public pools, and highway truck stops, often accompanied by a plodding two-step shuffle and grunting noises.

The Bopper was seen only once in corporeal form in 1969, shortly after the release of The Archies’ “Sugar Sugar”. A dog walker in Nesbit, Mississippi saw an unusual figure standing under an oak tree (near a location that would become the Jerry Lee Lewis Ranch in 1973). He was described as wearing a dark suit with a cruel, steel crown and having “his eyes bugged out and his face turned blue”.

The figure didn’t speak with his mouth, but the witness reported that the message was as clear as if he had sung through a Shure 55S microphone: “Hellooooo bayyyyybeeeeee!”

It’s The Truth Ruth

Trump Administration officials refused to comment on The Big Bopper Files, pivoting to a sales pitch for the White House’s newest memecoin, $DOOSEY.

Advocacy groups continue to urge that the threat of a backwater rock n’ roll lich needs to be taken seriously. Cindy Van Richten of the Southern Unholy Life Center warns that, “On this approaching anniversary of the day the music died and the start of his unlife, people in areas with significance to The Big Bopper may be at increased risk of attack or bodily possession. We want to stress, however, that anyone who ‘feels real loose like a long neck goose’ might just have avian flu.”

At this point, only the federal government knows how real a threat The Big Bopper poses, but the SULC and others are on record stating that if there is an 11+ Hit Dice Oldies musician wandering the countryside, the American public should know the truth.

Ronald Sampson